Open source license compliance distilled

Licenses are a fundamental part of open source but the challenge of finding and complying with the licenses can be daunting and mind-numbing. Here I summarize the practical license compliance landscape and set the scene for follow-up posts on how we can do better — to everyone’s benefit.

Generally speaking there are only three obligations that come with open source licenses:

- Attribution — Most licenses require that you attribute the copyright holders of the projects you use in your software. Typically, this is done in a NOTICE file included with your system. For many licenses, this is the only obligation.

- Component Source disclosure — Weak Copyleft licenses require you to make available the source of the components you use or modify such that the end user of your system can rebuild and replace the open source in your system.

- Full-Program Source disclosure — Strong copyleft licenses require you to also release the code for your entire program as similarly licensed open source in certain scenarios.

There can be other details, but the vast majority of situations involve a subset of these three obligations. It’s worthwhile to note that pretty much all of the obligations only kick in if you actually distribute the open source to others — using the code internally, even to run a customer-facing service, does not trigger the terms. Network or server licenses close that gap and have terms that trigger for any customer-facing use.

The landscape has gotten a bit more interesting lately with the advent of the Server-Side Public License (SSPL) and various Commons Clauses springing up. I’m going to set those aside here as they are not (currently) considered open source licenses so fall under whatever commercial procurement and compliance process you many have.

Compliance challenges

On the surface, compliance seems pretty straightforward — track what you’re using, get the licenses, read the terms, follow the (relatively few) instructions. In practice, it’s unfortunately not that easy.

What open source are you using?

Try this experiment, find a dev near you and ask them what open source is in their system. Some will, perhaps with a bit of digging, come up with a complete list. Others will mention only the top-level components. Still others will just shrug. Today with package managers like npm, and containers, it’s trivial for a dev to bring in thousands of open source component without even knowing it.

Some package managers make it easy to get an inventory of the open source in use by providing a lock file that lists all the packages or having a command line tool option to dump the inventory. Others are no help at all. What’s more, versions change all the time and since licenses and copyright also change between versions, it matters what version you’re using.

And of course, if you’re using source directly, you need manually track the origin of the source using one of several vendoring approaches.

What’s the license?

Given an inventory of open source at play, you need to figure out the related licenses. Many (many) repos on GitHub, packages in Maven etc. do not actually state a license. Sometimes they have one the repo but forgot to put it in the package. Other times the project team just didn’t know or see the point.

Basically, if there is no license then you have no rights to use the code. Either use something else or contact the project team and ask them to put a license on the code. Fortunately, it turns out that folks are generally quite keen to have their code used and so are happy for the pull request that adds a license.

Assuming you can find a license, the so-called envelope license problem may still be an issue. This is where the envelope (top-level of a repo, package metadata, …) identifies a license but the actual code has additional/different licenses. Frankly, this is just sloppiness on the project team’s part — they’re not really respecting the licenses of the code they’re using and are not enabling you to do so. Unfortunately, this is ultimately your problem as a downstream user — you are on the hook to comply because you are distributing the component.

The other major topic is snippets. Devs are lazy (in a good way) and happily copy and paste code from other projects or, famously, from Stack Overflow (there is even a book on that!). The challenge here is that those same devs often neglect to include the license of the original code or even cite where it came from. Snippets are pernicious buggers that are notoriously hard to find.

Understanding the terms

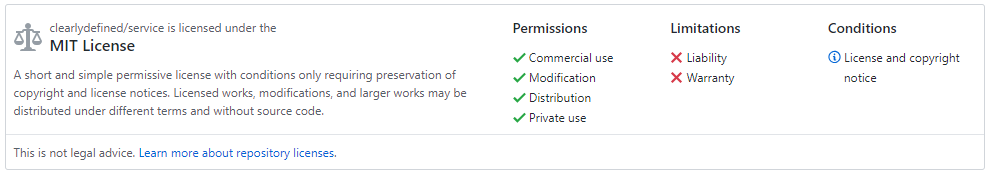

OK, so you know what you’re using and have found the licenses that apply, understanding the terms is the next step. Fortunately, there are numerous resources available to help there. tl;drLegal has good classifications of the licenses and obligations. GitHub helps you with similar info right on the repo itself. Just click the license indicator at the top right of the repo view (there is one, right? The project has a license, right?) to get license details as shown below. You want the Conditions column in this context.

There are some cases where some interpretation of the license and the usage scenario is required — in particular around copyleft disclosure requirements for different licenses and architectures. You’ll probably want some legal advice on those.

Who are the copyright holders?

With all the license terms sorted, you likely need to attribute the various copyright holders. Here we see open source projects all over the map as to if and how copyright holders are captured. Many licenses say something to the effect of “you must attribute the above copyright holders”. There might be one copyright holder for the entire project, or several per file. Some projects track people in a NOTICE, CONTRIBUTORS, or AUTHORS file. A note here, just ‘cause someone wrote the code does not mean they hold the copyright. I work for Microsoft and they get the copyright on everything I do at work in exchange for paying me. I’m fine with that but you need to attribute Microsoft not me.

Where’s the source?

This one is the bane of my existence. As mentioned in the Source disclosure discussion above, some licenses require you to make buildable versions the open source code available. Obviously if you’re using source and building it yourself, you have the source needed to do the disclosure. Users of packages however generally do not have that luxury — they are just getting binaries via a package manager. Somehow you’ve to go from knowing you’re using Foo 1.0 to knowing the corresponding commit in some repo. Yes, the commit matters.

Copyrights and licenses change over time and, well, you’re supposed to disclose the source and attribute copyright holders for the component you’re actually using, not some random version. That’s harder. If you’re lucky the project team put a Git tag that matches the version number of the package on the repo, or squirreled away the commit hash somewhere. Some publishing workflows like the one in npm make this really easy. Others, well, don’t.

And just for the record, most packages are not source — they have been compiled or modified in some way prior to packaging. For example, an npm looks like it might “be source” but these days many are transpiled from TypeScript, ES* with Babel, CoffeeScript, … Further, minifying and obfuscating is common and can strip copyrights and licenses, and create code that, itself not effectively modifiable. So, yes you may be able to read it but hey, I used to read 6502 machine code, that does not make it source or suitable for license compliance.

Knowing the source for what you’re using is not just a compliance topic. Source is of course needed if you want to build the open source you use, run additional IP or security scans, or have the code stashed away in the event that the repo disappears and a fix is needed.

Mono repos — one repo that produces many, sometimes hundreds of, packages — are an interesting challenge. You need to know not only the repo, but also where in the repo the source for a package lives. Sometimes this is explicitly called out, other times it’s implicit in a build configuration.

We spend a lot of time trying to find the matching source for the packages we use.

Wrap up

Well, that’s about it for the basics of open source license compliance. Not a great picture when laid out like that — thousands of components, hunting for information, license interpretation, … All up you need to use judgement, assess your risk tolerances, and understand the norms and intents of the communities you engage. Sometimes it can be challenging but, in the bigger picture, it’s typically a small price to pay for the great function you’re getting.

Fortunately, there are some efforts to make much of this easier. In the next few posts on this topic I’ll outline some open source work aimed at helping here.

Disclaimers

I am not a lawyer, I am not your lawyer, I have never played a lawyer on TV, and you can’t use my lawyer. That is, get your own legal advice.